From 23 June 2021 to 1 August 2021 I worked as an Artist-in-Residence at ArtsIceland of Ísafjörður in the Westfjords of Iceland.

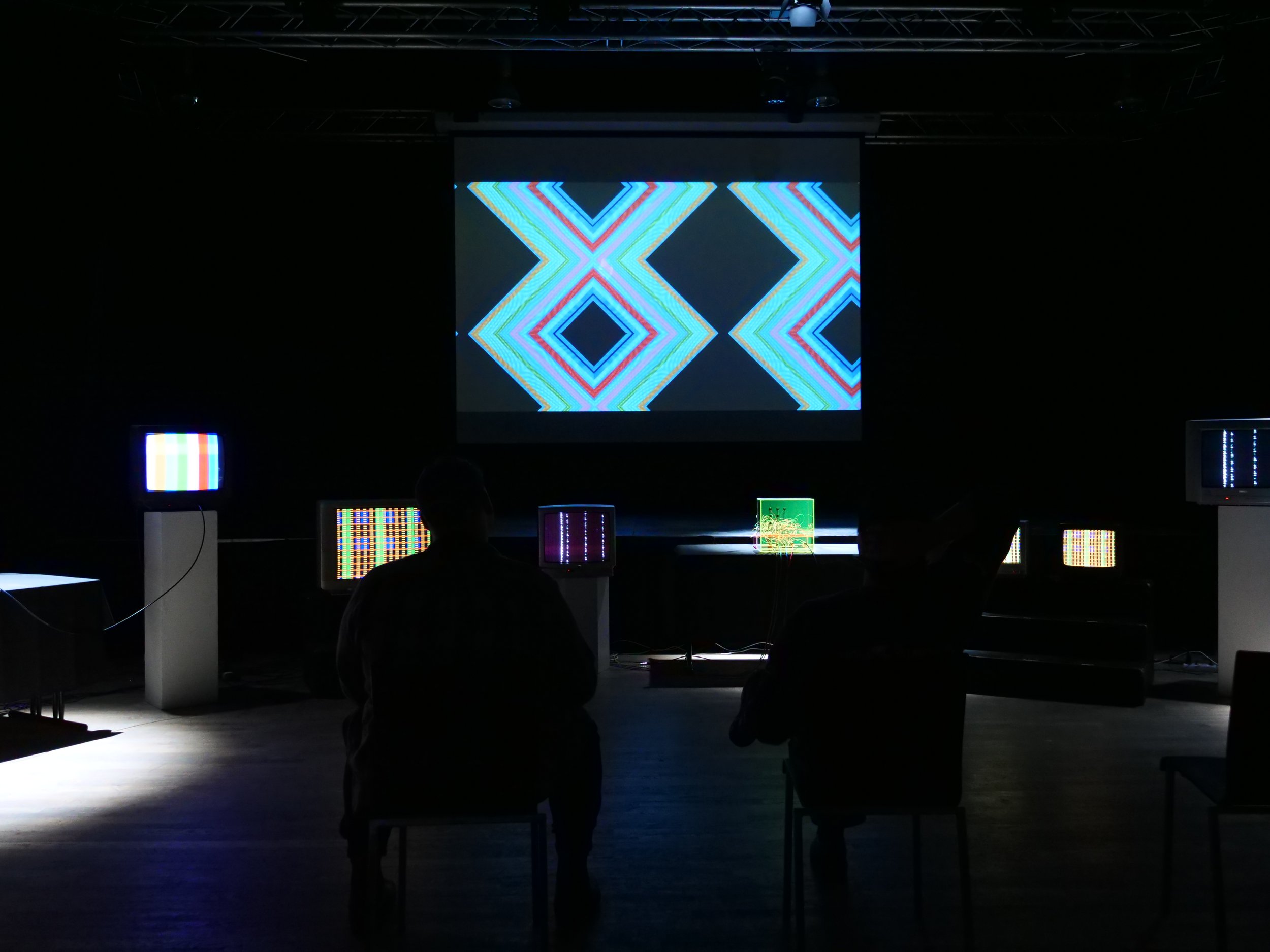

This residency culminated in an audiovisual installation - “Midnight Sun” - for custom-built audiovisual synthesizers, three channels of analog video, one channel of digital video, and eight channels of immersive audio.

As Pythagoras had it, the planets, in their periodic movements around the sun, produce harmonious sound. This is the time-honored idea of the music of the spheres. Mindful of this insight, Pythagoreans hear music in all kinds of periodic phenomena — the progression of seasons, the rhythm of tides, the melody of proportion.

Perceived by human standards, an exceptional instantiation of the music of the spheres is known as the “midnight sun.” This refers to the phenomenon, unique to summertime in polar regions, of broad daylight at local midnight. The tilt of the earth in its trip around the sun causes this phenomenon — a mundane explanation for a surreal experience.

For all its radical transformation of everyday life, from a cosmic perspective, there is nothing special about the midnight sun. We remain at roughly the same distance from our star, moving at the same speed, rotating at the same rate.

Perceived on this scale, the distinction between daytime and sub-polar diurnal cycles is more like a difference in timbre than it is of pitch. Bright and sharp, in contrast to the mellow alternation between day and night. An octave played by bells versus an organ.

This is not, of course, how we experience the midnight sun. Its effect on human beings is far more distinct. Unsurprising, given how ingrained the rhythm of day and night is in us. To think Western temperament for a moment, the midnight sun is more a perpetually-unresolved major seventh than it is a downward-tilting minor one.

More than unresolved, the midnight sun strikes us sub-arctic dwellers as “unnatural” — a violation of expectations conditioned by our everyday experience. This is why, when summer comes, folks flock to locations on earth where one can experience the midnight sun.

What this reaction highlights, however, is the artificiality of our concept of “nature.” For there is nothing unnatural about the midnight sun. It is simply the same phenomenon viewed from a different perspective, heard in a different voicing. The distorting effect of our anthropocentric projections onto reality — more to the point, the ethical imperative to transcend them — is the theme of my work.

Being in Iceland and not being Icelandic, one is hyper-conscious of the presence of tourists, and above all of one’s own tourist-hood. Tourism in Iceland is a major industry, and it’s easy to see why. Natural beauty is inescapable here.

In foraging for the “natural” ingredients of this work, I spent much time trying to remove the “human” element from my footage. In so doing, I often thought about why am I doing this.

Part of it had to do with the desire to transcend my own anthropocentric perspective. Yet it was also compositional decision. To allow the aesthetic dimensions of nature to come to the fore, you need to remove extraneous elements. And in this sense, humanity is extraneous.

In Iceland, one also becomes aware of the discreteness of sounds. So few sound-making things per square kilometer, every phonon is special. And living among the mountains of the Westfjords, every roundtrip made by a disturbance of the air is markedly audible.

Living in such an echo chamber gives you a newfound sense of your contribution to the symphony of molecules. It helps me understand our place within, rather than atop, a hierarchy of co-existent entities.

Once the tourist lens fades away, you become aware, in the Icelandic environment, of temporal processes that have taken place on macroscopic timescales.

This awareness does not come easy. Our human ability to synthetically perceive “beauty” in the form of patterns arranged in spatial simultaneity belies the supra-human forces that produced them, and the glacial intervals at which those forces were exerted.

This led me to reflect on another paradox, i.e. that synchronicity is not a property of reality but a conceptual filter applied to it by consciousness. The first lesson of general relativity is that there is no such thing, strictly speaking, as the same “instant” for two different entities — every event in the universe is separated by a discrete, nonzero spacetime interval.

A major affordance of recording technology, be it audio or video, is access to perceptual realms beyond our everyday experience. When employed in consort, these modalities — seeing and hearing — allow us to intuit phenomena that transcend sense materiality.

If the mountains of the Westfjords put our human conception of time in perspective, the same is true, on the other end of the spectrum, of analog video synthesis. Unlike digital processes, which may be conceived and executed as “simultaneities” (so to speak), composing for cathode-ray tubes induces appreciation for the precision needed to produce geometrical patterns from electronic oscillations.

The timescale of analog video is far more minuscule than anything we experience on a day-to-day basis. Yet the shapes it produces are entirely familiar, since we encounter them regularly in macroscopic reality. These include those as macroscopic as volcanic formations.

This, in short, is the animating idea of my work, which combines footage of natural phenomena of the Icelandic landscape with sound-image patterns generated by custom-engineered analog audiovisual synthesizers.

By placing the time scales these two elements embody — the macro-geological and the micro-synthetic — in counterpoint to one another, sympathetic resonances of geometrical harmony emerge. Time becomes legible in space, and space becomes temporal again. We hear the music in geometry, and see the geometry of music.

Such appreciation for magnitudes of scale lies beyond what we trivialize in postcards. By mining this realm, I aim to restore temporality to the reified landscapes that figure in so many photographs, thereby opening up a new way to experience their reality. In so doing, my intent is to bring about reflection on the macro-meteorological processes from which such structures originally emerged, and contemplation of humanity’s role in presently disrupting them.

In this regard, the fact that the installation makes use of CRT televisions, otherwise destined for the recycling center in Iceland (and elsewhere), is no coincidence. The teleological conception of technological development that drives our global economy produces a slew of obsolescent garbage, much of which is obsolescent only on account of the socially constructed need for newer and shinier things.

By repurposing outmoded technologies and reactivating the life left in them, I aim to challenge our conception of technological progress as a one-way highway, and gesture towards a different way of relating to technology, one less consumptive and more intentional.

Phenomenologists are known to hold that if a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, it does not in fact make a sound. And yet, to say that everything that exists exists for consciousness is not to say that conscious beings, least of all human beings, sit atop a hierarchy of existence. This is what I hear in the midnight sun.